Disability is not a bad word. Here’s why.

Disability is not a bad word. If you’ve stepped in or scrolled through disabled spaces the past few weeks, you may have seen this message plastered across a post or two, and for good reason. But what does it actually mean? Are we seeking to destigmatize a word or the disabled identity altogether?

Ugly Laws in America

Let’s provide some much-needed context first. It doesn’t take much digging around to see the historically horrible treatment of disabled folks in America and far beyond. Something like the Ugly Laws seems almost too absurd to be real - but it was. Through the mid-19th century and as recent as the 1970s, laws in the US denoted that anyone with an unsightly or ugly appearance could be simply arrested and removed from public areas (which ended up being a lot of immigrants, veterans, and people unable to work). It was simply illegal to be ugly and disabled. This is part of a centuries-long tactic to erase disabled people from public life so non-disabled folks do not have to acknowledge them. And that legacy still continues today in the ways we talk about disability.

Defining (and Expanding) Disability

Disability is also a wide spectrum. There’s no right or wrong way to be disabled. Disabilities can affect our senses, movement, thinking, learning, communicating, and much more! Intellectual and developmental disabilities like Autism, ADHD, and Cerebral Palsy impact a person’s ability to learn, develop, and interact with others. Physical disabilities like limb differences, brain injuries, and respiratory disorders affect a person’s stamina, mobility, and ability to navigate themselves in the world. Behavioral or emotional disabilities like anxiety disorders, DID, and depression affect our ability to maintain relationships and foster a strong sense of well-being. Just like any marginalized identity, there are those who are more impacted and those who are less impacted in a community. It’s important to center those more impacted or require higher support, but that doesn’t have to come at the expense of invalidating those with less apparent disabilities. If you’re disabled sometimes, you’re still disabled. Yes, more visibly disabled people experience increased harassment and marginalization. So by including a wider spectrum of disability in our definition, we start to neutralize and normalize talking about accommodations and disability.

There are also countless ways of defining what it even means to be disabled. The CDC says, “A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).” This medical model views disability as a defect or illness that resides within the individual. Not my favorite, but this model has been used to advocate for finding treatments for more debilitating disabilities. The economic model views disability as our inability to work. Also not a great way of measuring disability, but this did give us disability benefits for those who can’t work. The social model says we are not disabled individually, but as a result of societal barriers and attitudes. And while I don’t find this model to be true for me, it also advocates for more accessibility in public spaces and is the backbone of The Americans with Disabilities Act. You know how workplaces can’t fire you for simply being disabled? That hospitals must offer reasonable accommodations to treat disabled people? Or ramps and accessible entry points being required for most public spaces? It’s kind of a big deal. The thing is, none of these models are complete or quite right on their own, but they give us a multi-faceted approach to viewing disability as a sociopolitical term that is up to each person to define.

Disability Has No Moral Value

The bulk of conversation around disability today is often intentionally made more palatable for non-disabled folks through euphemisms, or words meant to communicate something in a less harsh way. “They’re not disabled, they’re differently-abled!” “They have super powers!” “They have special needs!” But all these are simply attempts to avoid saying the word ‘disabled’. Why can’t we say that word? Despite centuries of advocacy and disability rights activists expressing direct approval for this term, why is it still taboo to say disabled? That’s on ableism.

There’s no doubt disability can make your life harder in many ways. It’ll take you 30 minutes longer to get ready because you’re searching online to find a store that has an accessible bathroom. You’ll be in public, and a random person will go up to you and ask why you’re using a cane even though “you’re young and healthy!” as if that’s their business. The act of being disabled is not morally bad or good. It’s neutral. You are not morally inferior or superior for being disabled or non-disabled. Disability is the act of simply not being able to do something because of impairments to your body and/or mind.

In a capitalist society that is quite literally built around our ability to work and contribute monetarily, we see any inability as flawed or less than. Our worth is absolutely inherent as humans, not something that is contingent on our abilities. (That’s why asking for help can bring up so much shame and guilt.) Until we are able to separate our inherent worth as humans from our ability to create and do things, we will always have an issue with acknowledging disability neutrally. But that’s exactly what it is, neutral.

Disability is not a tragedy either. Many folks have a skewed perspective of what it means to be disabled. That being disabled means your life is devoid of joy, fulfillment, or love. It’s not. Stop using us as inspiration porn. At the same time, to have confidence as a disabled person, not in spite of it, is radical. In a world where it has quite literally been illegal to be disabled, dodging ableist remarks feels like an olympic sport. Finding joy and community in a world where your healthcare, safety and respect is a topic of debate, disabled joy and disabled autonomy is a radical and necessary thing.The reality is, most non-disabled people will not assume you are confident, that you are worthy, that you are whatever positive adjective, unless you directly show it to them. And that’s not always enough either. More often than not, you have to be the first one to advocate for yourself and that requires a lot of energy, skill, and confidence - a burden that I wish we didn’t have to carry.

Skip the Euphemisms

If we only see disability as a difference or a special way to do something, we erase the struggles that disabled folks have with everyday tasks and the systemic barriers that make our lives harder. Something as simple as unloading the laundry can take hours. Making a home-cooked meal takes days of planning. Need disability benefits? Then you can’t have more than a few thousand dollars in assets. Make more than that? Well now you can’t afford your benefits out of pocket.

The use of euphemisms ignores all the ways in which society fails us and denies respect, rights, and agency based solely on our ability to work or produce. If we can’t address disability as a hardship existing in the first place, we’ll never be in a place to rectify the wrongs of the past and build a more equitable world for disabled folks in the future. We need your support this month and every month! And that goes far beyond just naming disability, but showing up for us as our rights continue to be under attack in legislation and beyond.

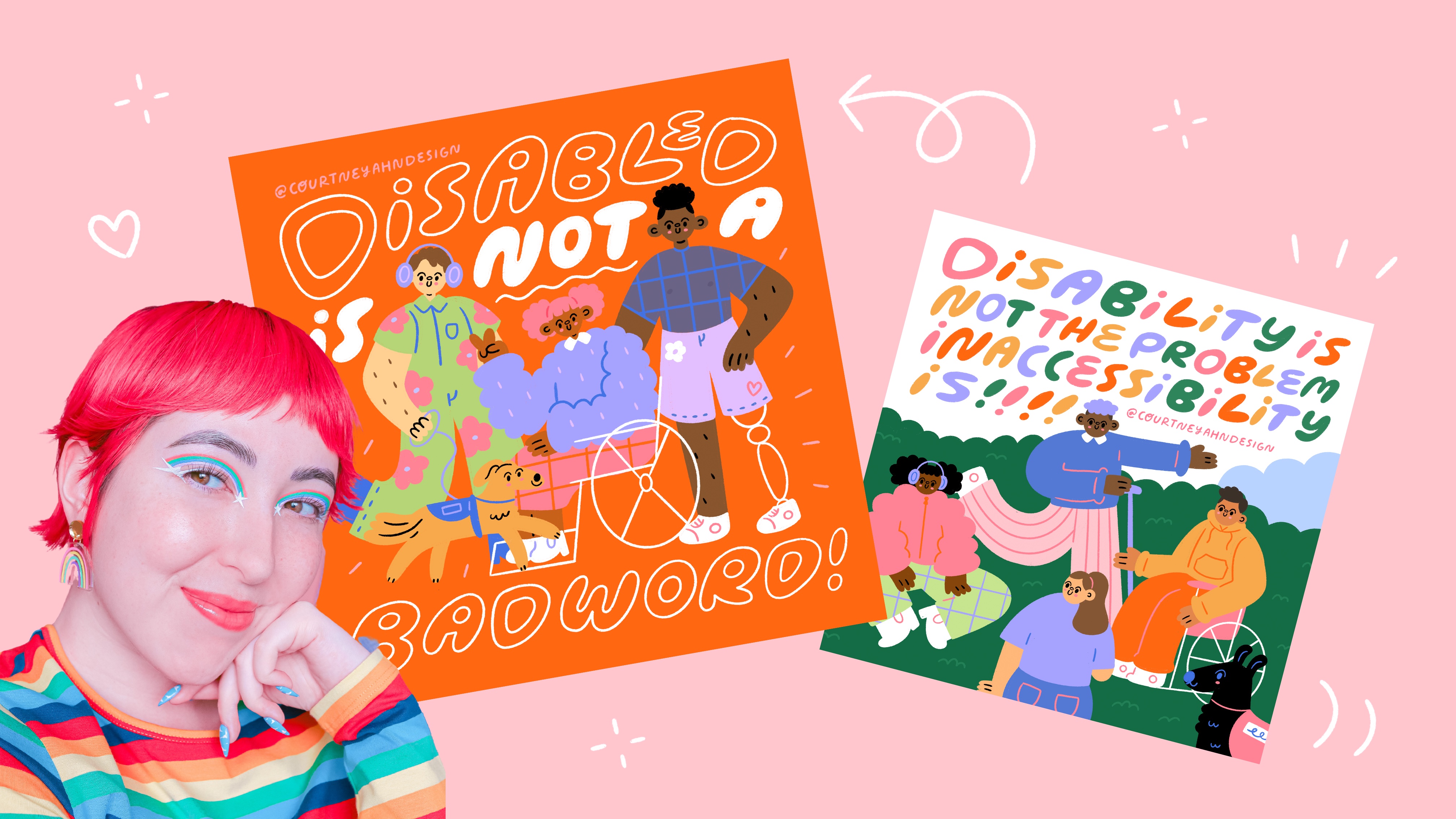

About the author: Courn Ahn (they/them) is a queer, Korean-American, and multiply disabled non-binary designer and illustrator. They’re a 3-time published children’s book author who is proud to have worked with Oregon Education Association, KinCultivate, APANO Action Fund, and many other advocacy centered organizations. Follow Courn’s Instagram where they post whimsical and powerful illustrations about dismantling systems of oppression and amplifying community care.

We feature community voices about the issues that matter to Asians Americans, allies and the communities who share our aspirations. Have something you want to say? Reach out to comms@apano.org.

Disability is not a bad word. If you’ve stepped in or scrolled through disabled spaces the past few weeks, you may have seen this message plastered across a post or two, and for good reason. But what does it actually mean? Are we seeking to destigmatize a word or the disabled identity altogether?

Ugly Laws in America

Let’s provide some much-needed context first. It doesn’t take much digging around to see the historically horrible treatment of disabled folks in America and far beyond. Something like the Ugly Laws seems almost too absurd to be real - but it was. Through the mid-19th century and as recent as the 1970s, laws in the US denoted that anyone with an unsightly or ugly appearance could be simply arrested and removed from public areas (which ended up being a lot of immigrants, veterans, and people unable to work). It was simply illegal to be ugly and disabled. This is part of a centuries-long tactic to erase disabled people from public life so non-disabled folks do not have to acknowledge them. And that legacy still continues today in the ways we talk about disability.

Defining (and Expanding) Disability

Disability is also a wide spectrum. There’s no right or wrong way to be disabled. Disabilities can affect our senses, movement, thinking, learning, communicating, and much more! Intellectual and developmental disabilities like Autism, ADHD, and Cerebral Palsy impact a person’s ability to learn, develop, and interact with others. Physical disabilities like limb differences, brain injuries, and respiratory disorders affect a person’s stamina, mobility, and ability to navigate themselves in the world. Behavioral or emotional disabilities like anxiety disorders, DID, and depression affect our ability to maintain relationships and foster a strong sense of well-being. Just like any marginalized identity, there are those who are more impacted and those who are less impacted in a community. It’s important to center those more impacted or require higher support, but that doesn’t have to come at the expense of invalidating those with less apparent disabilities. If you’re disabled sometimes, you’re still disabled. Yes, more visibly disabled people experience increased harassment and marginalization. So by including a wider spectrum of disability in our definition, we start to neutralize and normalize talking about accommodations and disability.

There are also countless ways of defining what it even means to be disabled. The CDC says, “A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).” This medical model views disability as a defect or illness that resides within the individual. Not my favorite, but this model has been used to advocate for finding treatments for more debilitating disabilities. The economic model views disability as our inability to work. Also not a great way of measuring disability, but this did give us disability benefits for those who can’t work. The social model says we are not disabled individually, but as a result of societal barriers and attitudes. And while I don’t find this model to be true for me, it also advocates for more accessibility in public spaces and is the backbone of The Americans with Disabilities Act. You know how workplaces can’t fire you for simply being disabled? That hospitals must offer reasonable accommodations to treat disabled people? Or ramps and accessible entry points being required for most public spaces? It’s kind of a big deal. The thing is, none of these models are complete or quite right on their own, but they give us a multi-faceted approach to viewing disability as a sociopolitical term that is up to each person to define.

Disability Has No Moral Value

The bulk of conversation around disability today is often intentionally made more palatable for non-disabled folks through euphemisms, or words meant to communicate something in a less harsh way. “They’re not disabled, they’re differently-abled!” “They have super powers!” “They have special needs!” But all these are simply attempts to avoid saying the word ‘disabled’. Why can’t we say that word? Despite centuries of advocacy and disability rights activists expressing direct approval for this term, why is it still taboo to say disabled? That’s on ableism.

There’s no doubt disability can make your life harder in many ways. It’ll take you 30 minutes longer to get ready because you’re searching online to find a store that has an accessible bathroom. You’ll be in public, and a random person will go up to you and ask why you’re using a cane even though “you’re young and healthy!” as if that’s their business. The act of being disabled is not morally bad or good. It’s neutral. You are not morally inferior or superior for being disabled or non-disabled. Disability is the act of simply not being able to do something because of impairments to your body and/or mind.

In a capitalist society that is quite literally built around our ability to work and contribute monetarily, we see any inability as flawed or less than. Our worth is absolutely inherent as humans, not something that is contingent on our abilities. (That’s why asking for help can bring up so much shame and guilt.) Until we are able to separate our inherent worth as humans from our ability to create and do things, we will always have an issue with acknowledging disability neutrally. But that’s exactly what it is, neutral.

Disability is not a tragedy either. Many folks have a skewed perspective of what it means to be disabled. That being disabled means your life is devoid of joy, fulfillment, or love. It’s not. Stop using us as inspiration porn. At the same time, to have confidence as a disabled person, not in spite of it, is radical. In a world where it has quite literally been illegal to be disabled, dodging ableist remarks feels like an olympic sport. Finding joy and community in a world where your healthcare, safety and respect is a topic of debate, disabled joy and disabled autonomy is a radical and necessary thing.The reality is, most non-disabled people will not assume you are confident, that you are worthy, that you are whatever positive adjective, unless you directly show it to them. And that’s not always enough either. More often than not, you have to be the first one to advocate for yourself and that requires a lot of energy, skill, and confidence - a burden that I wish we didn’t have to carry.

Skip the Euphemisms

If we only see disability as a difference or a special way to do something, we erase the struggles that disabled folks have with everyday tasks and the systemic barriers that make our lives harder. Something as simple as unloading the laundry can take hours. Making a home-cooked meal takes days of planning. Need disability benefits? Then you can’t have more than a few thousand dollars in assets. Make more than that? Well now you can’t afford your benefits out of pocket.

The use of euphemisms ignores all the ways in which society fails us and denies respect, rights, and agency based solely on our ability to work or produce. If we can’t address disability as a hardship existing in the first place, we’ll never be in a place to rectify the wrongs of the past and build a more equitable world for disabled folks in the future. We need your support this month and every month! And that goes far beyond just naming disability, but showing up for us as our rights continue to be under attack in legislation and beyond.

About the author: Courn Ahn (they/them) is a queer, Korean-American, and multiply disabled non-binary designer and illustrator. They’re a 3-time published children’s book author who is proud to have worked with Oregon Education Association, KinCultivate, APANO Action Fund, and many other advocacy centered organizations. Follow Courn’s Instagram where they post whimsical and powerful illustrations about dismantling systems of oppression and amplifying community care.

We feature community voices about the issues that matter to Asians Americans, allies and the communities who share our aspirations. Have something you want to say? Reach out to comms@apano.org.

Latest News

.png)